The implications of peaking workforces in a deglobalizing world

How will declines in working-aged populations affect the global economy?

Labor, the heart of production and consumption is declining in many of the world's largest economies.

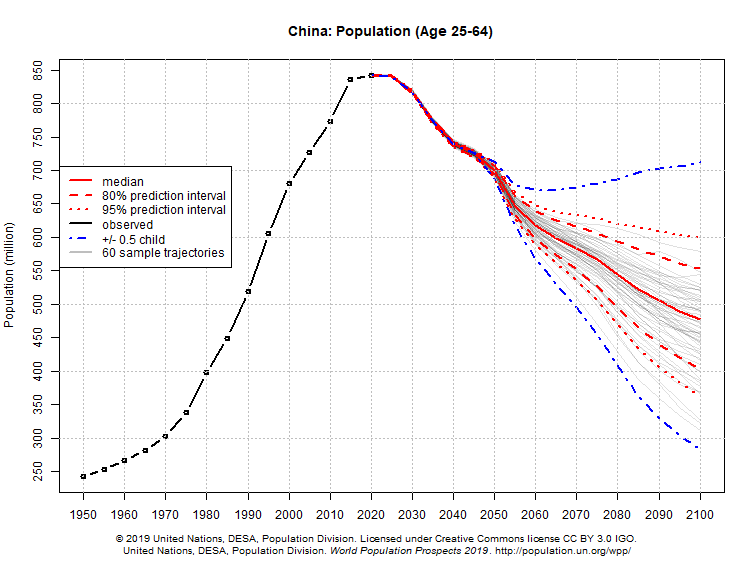

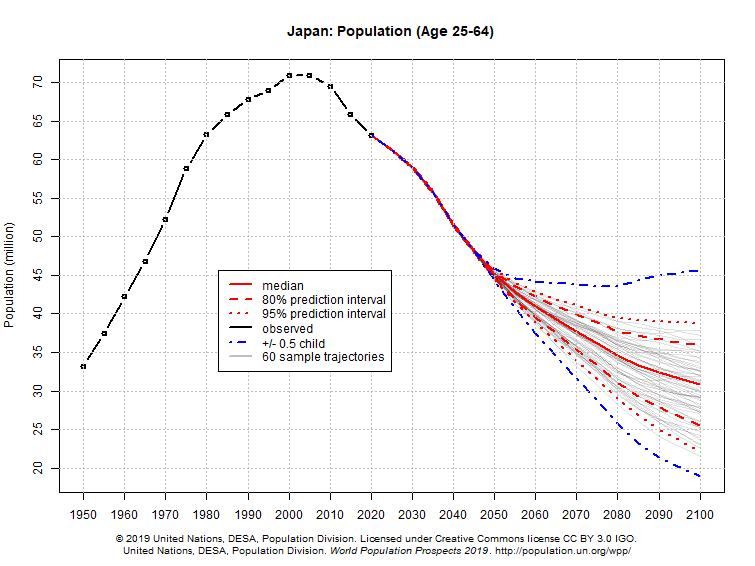

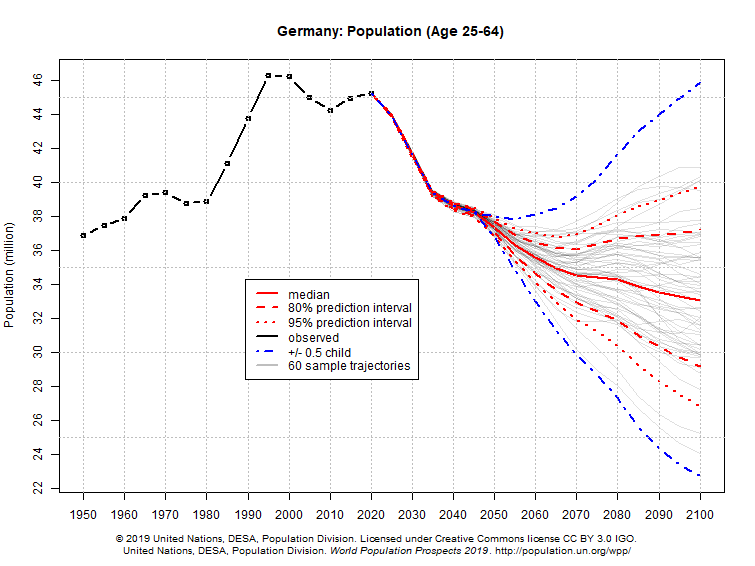

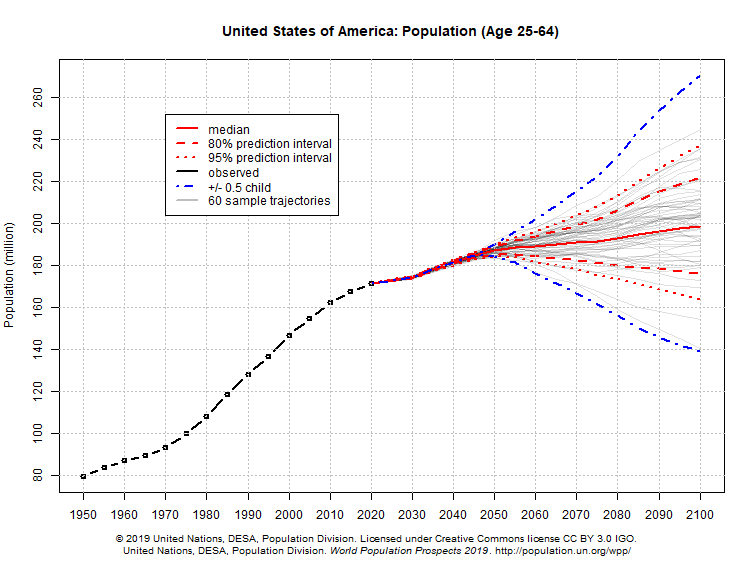

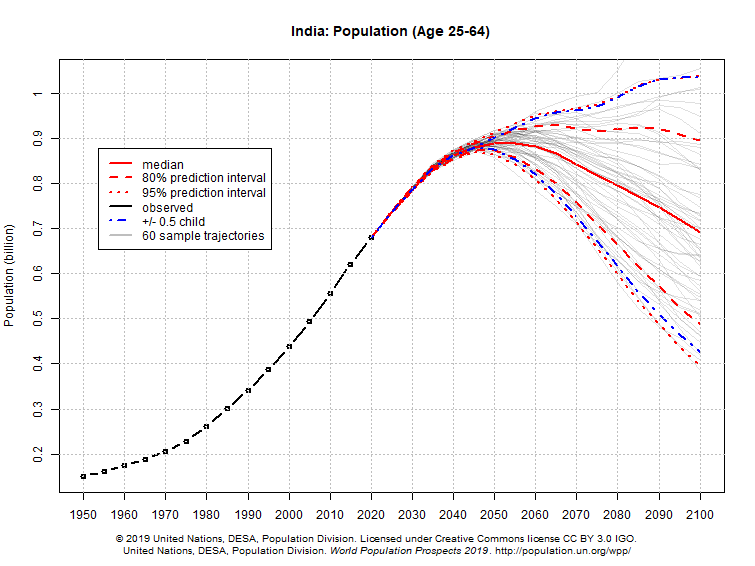

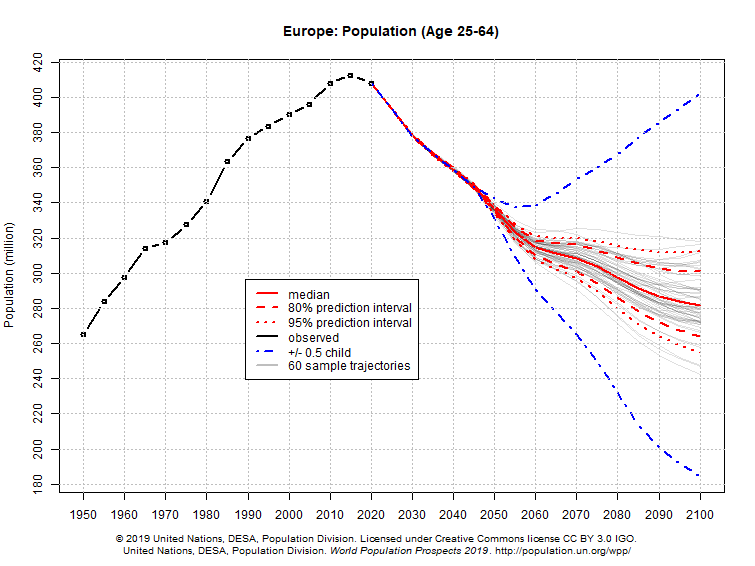

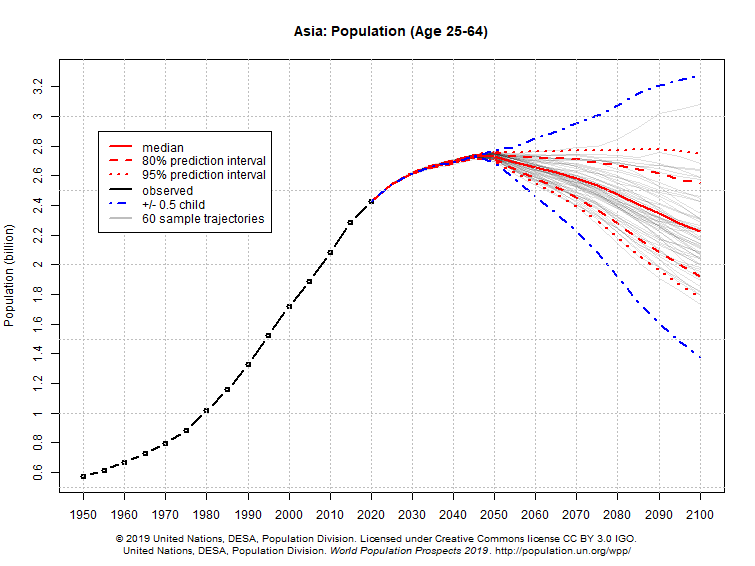

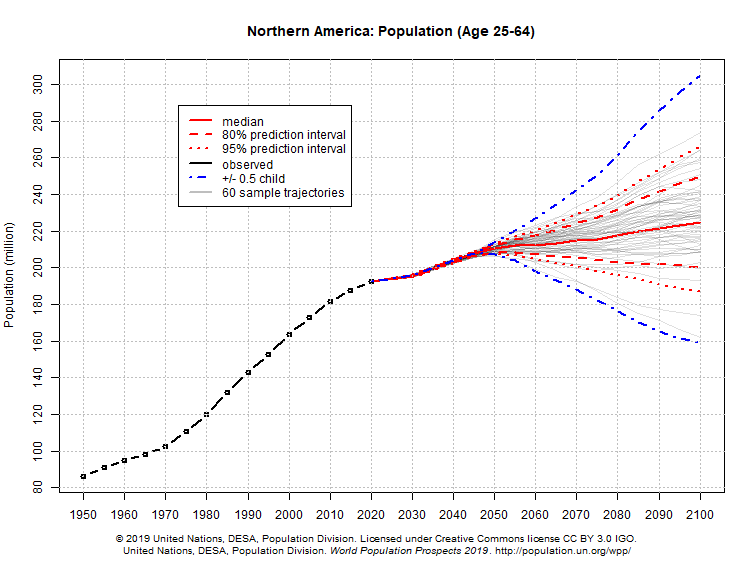

I compiled UN data showing how the primary working and consuming ages (25–64) grew in various countries since WW2 and where it’s projected to go.

Let’s look at how the top world economies compare.

The working-age population of “the world’s factory” and second largest economy is peaking now.

The third largest global economy’s labor force peaked around the global financial crisis and is entering a rapid decline.

The fourth biggest economy’s workforce population peaked around the dot-com bubble, rebounded, and is now entering a steep decline.

Where are working-age populations growing?

The working-age population of the largest economy, The United States, is projected to modesty rise for the rest of the century.

The fifth largest economy’s working-age population looks the best so far, with high growth for at least another 1–2 decades.

The United States, India, Australia, Egypt, Philippines, Indonesia, Israel, Norway, Sweden, New Zealand, South Africa, Mexico, Argentina, Canada, Nigeria, and Pakistan have strong working-age population growth prospects relative to the size of their economies.

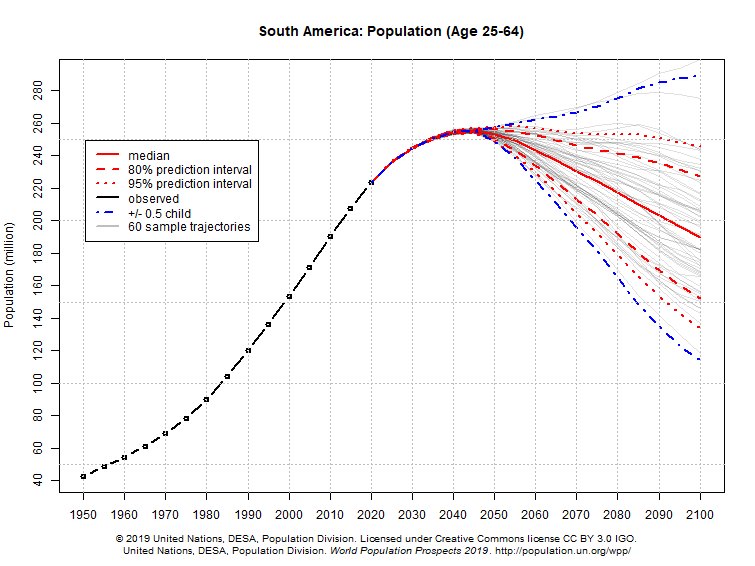

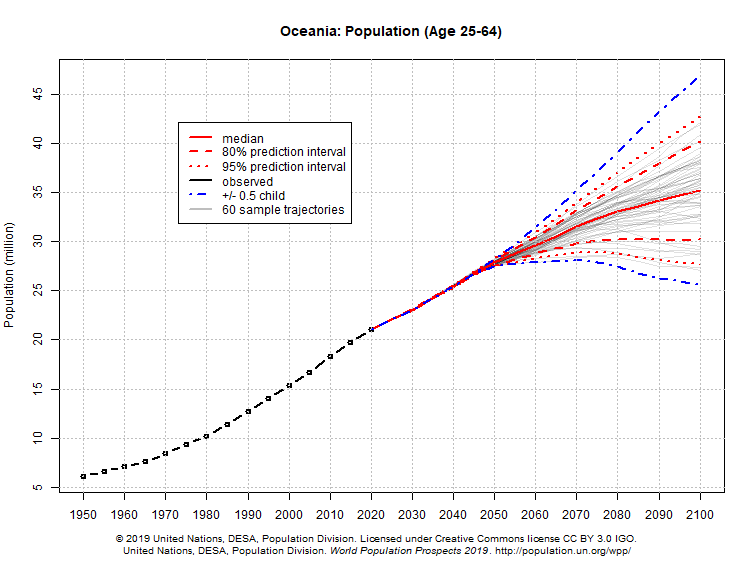

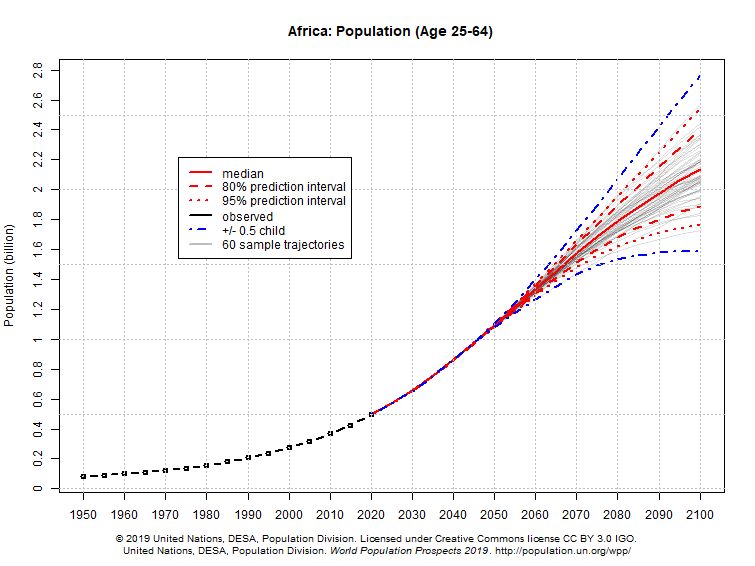

Now, let’s look at how the world's continents look.

Europe’s working-age population looks like it’s beginning a rapid decline, which Asia could join around 2050. North America’s working-age population looks relatively strong in comparison.

South America’s working-age population looks similar to Asia’s. Oceania and Africa look like they have the best prospects.

Unfortunately, if you believe NOAA climate models, many of the regions with the best trajectory are located in areas that climate change will potentially disrupt the most in the coming decades.

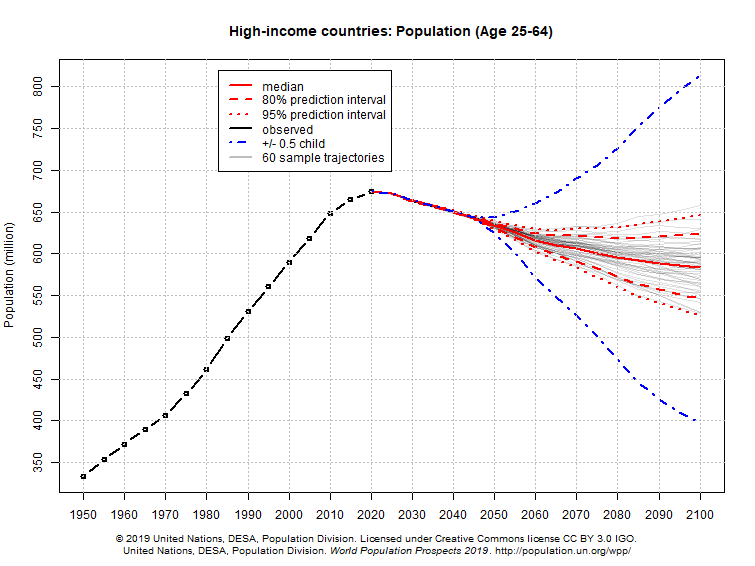

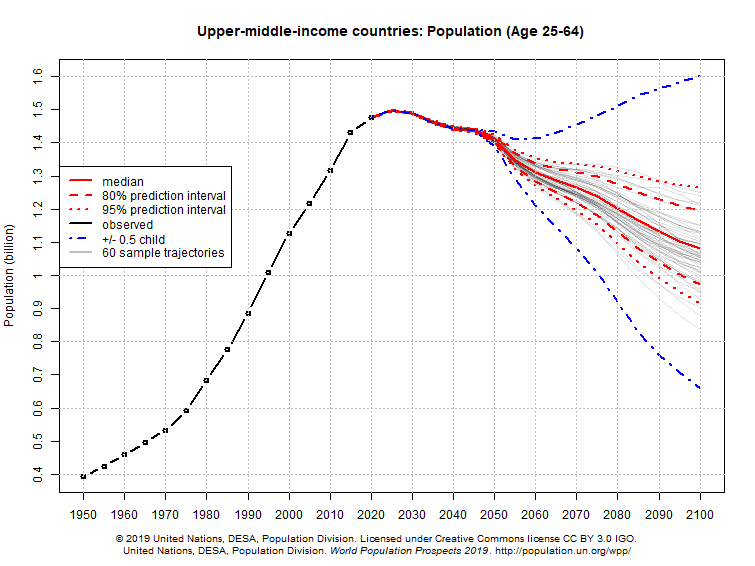

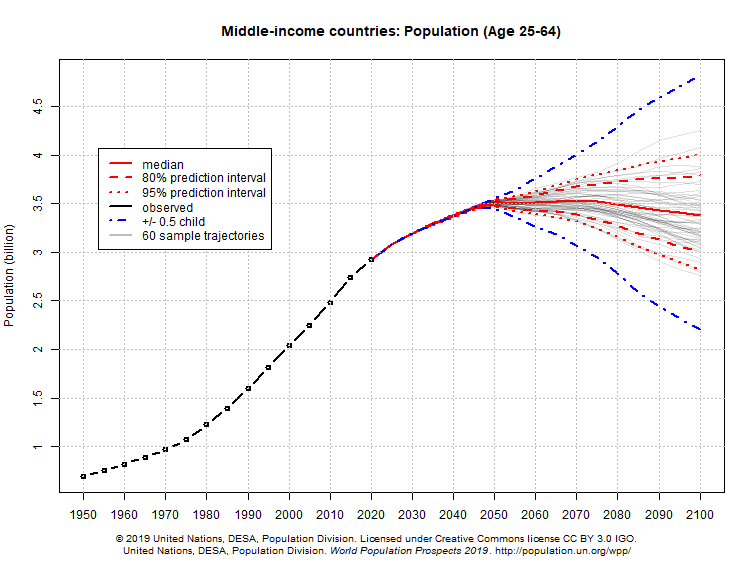

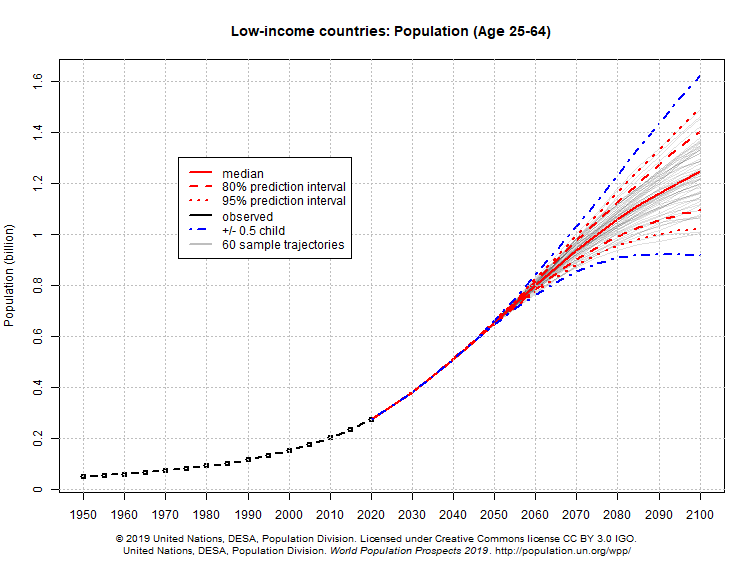

Now, let’s look at how the working-age populations compare based on income level.

The working-age population of high-income countries looks like it topped out in 2020, and upper-middle-income countries will likely peak around the middle of the decade.

Projections show that the working-age population of middle and low-income countries will continue to grow for decades.

What does all this mean for the global economy?

Will contracting workforces lead to greater inflation because of lower production and higher labor costs, or will it lead to disinflation or deflation due to lower demand?

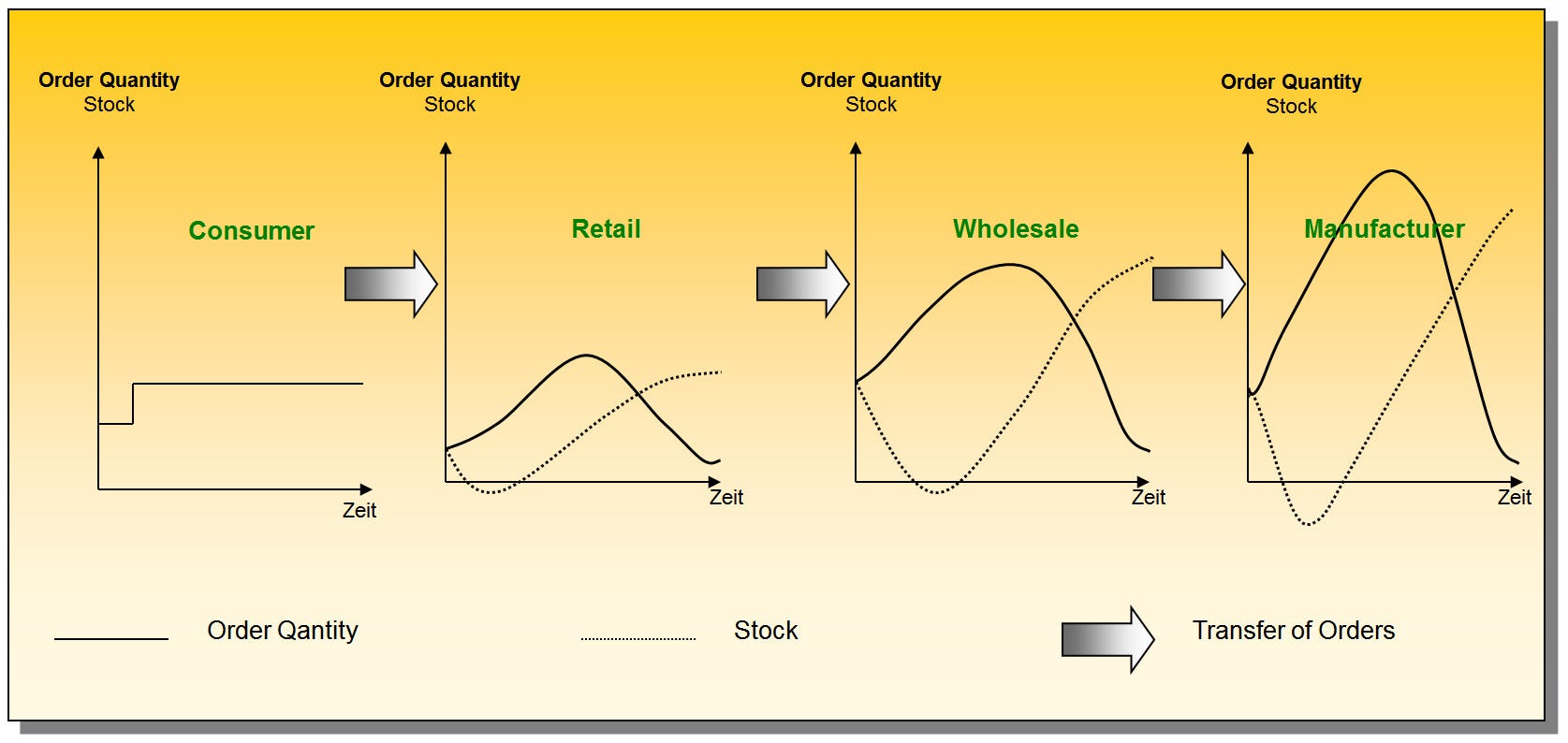

Both inflationary and deflationary forces could oscillate in unpredictable ways. Small fluctuations in supply chains could result in larger variability as the bullwhip effect takes shape.

80 percent of global trade is estimated to involve U.S. dollars. Fighting inflation in the United States can put pressure on foreign currencies.

Foreign entities must raise dollars if a global dollar shock occurs, resulting in US-denominated asset sales.

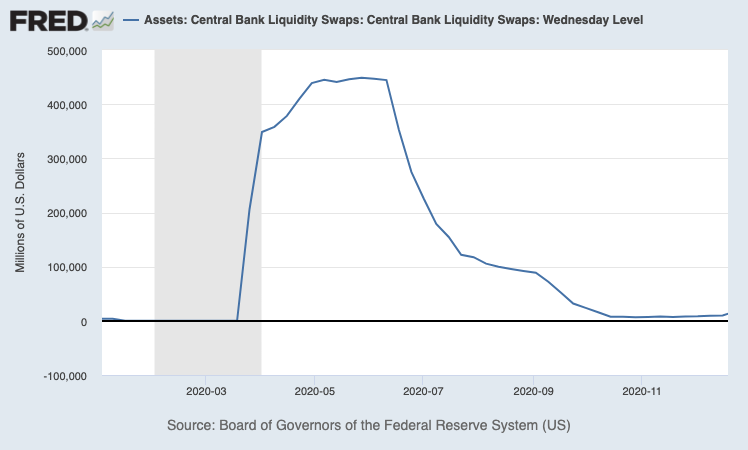

This selling pressure could be one of the reasons why the Fed initiated liquidity swaps with foreign central banks during the 2020 Covid panic. These liquidity swaps provided the dollars those economies needed and prevented further selling of US assets, putting a floor under the equity and bond markets.

This dynamic is why the U.S. monetary authorities (the Fed) bailed out Mexico, Australia, Brazil, Denmark, Korea, Norway, New Zealand, Singapore, and Sweden as one of their first measures when the 2020 crisis hit in March.

However, the 2020 covid shock was a lot different from the supply-driven inflationary environment the world is in now. The end of lockdowns is increasing employment and demand, but supply chains haven’t yet normalized.

Things might never normalize. The working aged population of the majority of the major world economies peaked during the covid crisis. No one knows what will happen next.

I hope to find the time and motivation to continue to explore global-macro topics. Please like and subscribe if you find this article interesting and want me to continue writing. Thank you.